Last week the article, “The case against pets: Is it time to give up our cats and dogs?” came across my desk from a number of different people. They sent it to me, not because I have cats, but for a couple of other reasons. First, one of the researchers quoted, Jess Du Toit, is a graduate student working on animal ethics in my Department’s PhD program. Second, my work on imperfect veganism frequently engages with the questions of where to draw the line. Jess says smart things in this article, such as pointing out that, at least in “the West,” pets are frequently considered companions or even family members. She also thinks that they fare better, more likely to receive appropriate care and treatment, when we consider ourselves not to be “owning” them but rather to be “caring for” or “keeping” them.

Today I want to focus on the second reason people sent me the article: drawing the moral line–not only where pets are concerned, but in general. We all draw moral lines in different places. The question in the article’s title caused as visceral a “NO!” in me as I’m sure the suggestion to give up eating Greek yogurt or bacon or prime rib or bluefin tuna causes in some others. To me, giving up Rosie and Lily is unthinkable–especially if it’s for some assumed moral wrong. To the neighbour down the hall, giving up buffalo wings during happy hour or the sausage and eggs breakfast special at the local diner might be just as unthinkable. Again, they might balk at the idea that there is a moral dimension to their food choices.

And even when we draw the line “here” rather than “there,” we compromise. Vegetarians go so far but no further, even if they think there are reasons to go further. Rosie and Lily are rescue cats whose life would have been much harder on the street. On balance the life they lead with me keeps them safer. They are indoor cats who never get to hunt and roam in their preferred outdoor environment. But it also saves a good number of birds and wildlife. Environmental groups cite research showing that outdoor cats threaten biodiversity and have contributed to the extinction of 63 species. Cats are the number one threat to birds, killing 2.4 billion per year. My rescue agency made me sign a contract agreeing that I’d keep Lily and Rosie as indoor cats.

Then there is the food. Unlike dogs, cats are “obligate carnivores” who require meat to be healthy. So yes, I feed my cats animal products despite that I am vegan. The meat in the food they eat is from factory farming, made of by-products usually deemed unfit for human consumption.

Do I wish there was another way? Yes. But I am as yet unaware of what that might be, short of not having cats at all. And that seems like too much to ask.

In moral philosophy we have this thing we call “the demandingness objection.” It’s usually offered against utiliarianism’s requirement always to bring about the best outcome. But we might understand the essence of it as this: a moral requirement might seem justified by the evidence but it is “too demanding” and, therefore, unreasonable. Clearly humans can rationalize all sorts of things, so it’s not enough just to go with our gut reaction about what is “too demanding.” Moral theorists propose various considerations that can be helpful in figuring out how we might balance apparent tensions that tug at what we hold dear (how to think all of this through is a veritable academic industry!). Usually these have to do with the relative weight of what we might be asked to sacrifice compared to what someone else might sacrifice. For example, if I can save a life but it means I’ll get mud on my favourite shoes, then it seems obvious I should get the mud on the shoes.

Most cases are more complicated than a life versus muddy shoes. When I think about Rosie and Lily, for example, I consider that they have a better life with me than they would have had in the colony of feral cats from which they were rescued as very young kittens, that for better or worse they are dependent on me for their care, and that they have certain nutritional needs that include animal products. Moreover, and more selfishly, they are great companions whom I love dearly, and there is nothing like the little surges of joy they inspire throughout the day. That sense of connection and companionship adds greatly to my own well-being and, arguably, have made me a more humane and loving individual. Those factors all speak in favour of me keeping them in my home and continuing to feed them as I do.

Here it’s not just that giving them up is “too demanding,” but that there are actually fairly compelling considerations in favour of continuing to have them in my life as companion animals. So I’m not yet convinced that we shouldn’t have pets. I have drawn a line.

Here is where the idea of imperfection comes in: I recognize that feeding my cats animal products points to an inconsistency in my practice. Yes, there are reasons that support my choice. I’m relatively comfortable with it, given the alternatives. What I do not conclude, however, is that this somehow means that there are no areas where I can do better. The key idea here is: what is the moral cost of the alternatives and how do they compare?

Going back to the earlier example, clearly I should save a life even if it means getting mud on my shoes. We make various trade-offs. People who continue to eat animal products regularly (quite possibly at every meal), put more weight on “I like cheese” than on the lives of dairy cows and more weight on “I can’t give up bacon” than on the lives of pigs. That’s a simple observation of what the repeated choice in the direction of those animal products says about someone’s moral commitments. Philosophers Dan Hooley and Nathan Nobis call this type of reasoning “the tyranny of taste.” They don’t think it’s justified.

I’m not a subjectivist when it comes to moral principles. I do think there are objective considerations that we ought to take seriously. But nor do I delude myself that it is always a simple matter to resolve when we have strong competing interests that pull us in different directions. And the fact is, morality IS demanding. It asks a lot of us in a very complex world where the possibilities for moral engagement sometimes feel endless. Samantha suggested to me that people might not want to start down a particular moral path (e.g. veganism) for fear of where they might end up. What about vegan knitters who don’t want to forgo wool? What about vegan cat lovers who don’t want to give up their fur babies? What about…[insert endless difficult sacrifices here]. But we can do it imperfectly.

And there may be different angles on the idea of our lives as, among other things, moral undertakings. Last week Shelley commented on the post about moral reasons, offering an idea derived from Foucault: “one can think of one’s life as a work of art and one’s decisions as a way in which to cultivate the self as an ongoing work of art and creation. More broadly, this understanding of morality relies upon a notion of power as productive rather than (merely) constraining.”

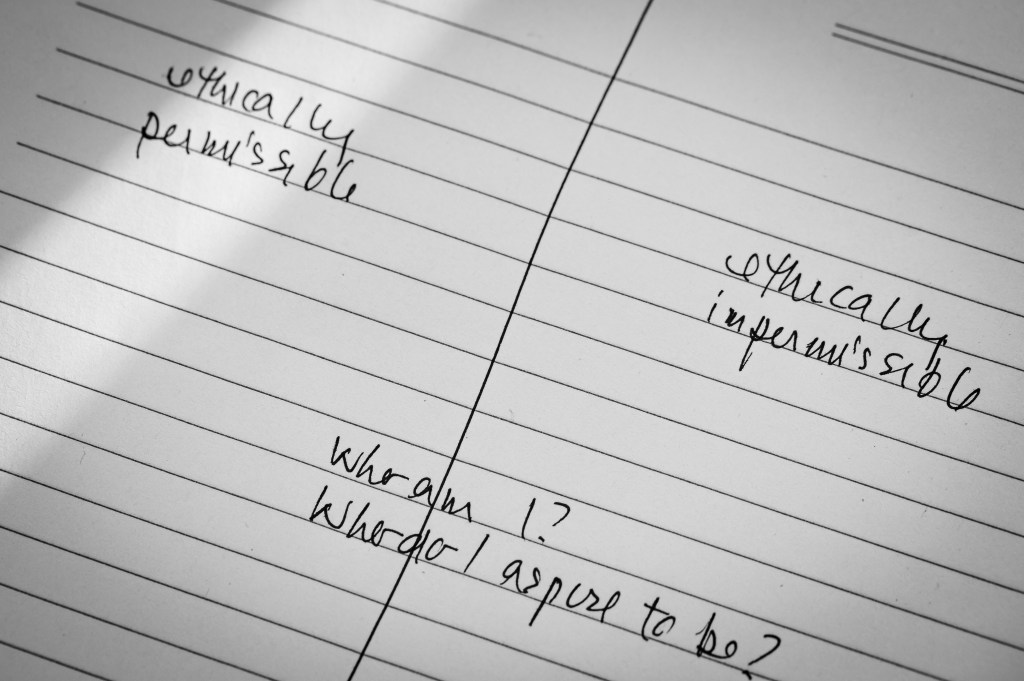

To simplify (perhaps to oversimplify), we might think of our moral commitments as demonstrating the person we want to be (or think we are), as broadly exemplifying our values. I’m not a virtue theorist and I lean strongly to the “moral constraints/moral permissions” idea of morality. But I care a lot about integrity and, as do most of us, I like to think of myself as a good person. So this general idea resonates quite strongly with me.

I think it’s a helpful way of thinking about where we draw moral lines. What does drawing a line “here” rather than “there” say about the person I am or the person I aspire to be? How do I engage with people who are drawing the line differently, making concessions and compromises in other ways than I am? At what point does a compromise feel too compromising, creating so much discomfort that I need to think it through some more? The moral hope I have in promoting the idea of imperfect veganism is not that people will stop drawing moral lines, but that they will think about the moral lines they draw and why they draw them where they do. This goes for me too.

Leave a comment